Maple, Elm and Oak

Policymakers say they're prioritizing Main Street over Wall Street. They should focus on independent contractors along America's side streets, too.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, in an appearance this month at the Economic Club of New York, had a simple message for Americans about the Trump-Vance administration’s priorities:

“Wall Street’s done great, Wall Street can continue doing well. But this administration is about Main Street.”

The administration sent a similar message from the swearing in of newly confirmed U.S. Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, with the president of the International Franchise Association on hand for the event. He has done a great job advocating for the franchise business model, which has been under attack right alongside the independent-contractor business model. His presence was the administration’s way of giving a nod to what most Americans think of as Main Street small businesses with storefronts—everything from fast-food restaurants to hardware stores to fitness centers—that can involve franchising:

All of that is movement in the right direction by the new administration, but there has been a glaring omission so far in its approach to putting hardworking Americans first: Not once has the White House made clear that it intends to protect independent contractors.

This omission is consequential, and it’s easy to fix. It would be a huge missed opportunity if this omission starts to leak into policymaking next.

Independent contractors are the smallest of small-business owners, often operating without any employees at all. We are what the government sometimes refers to as “nonemployer firms.” According to the U.S. Census, nonemployer firms contribute $1.3 trillion a year to the economy.

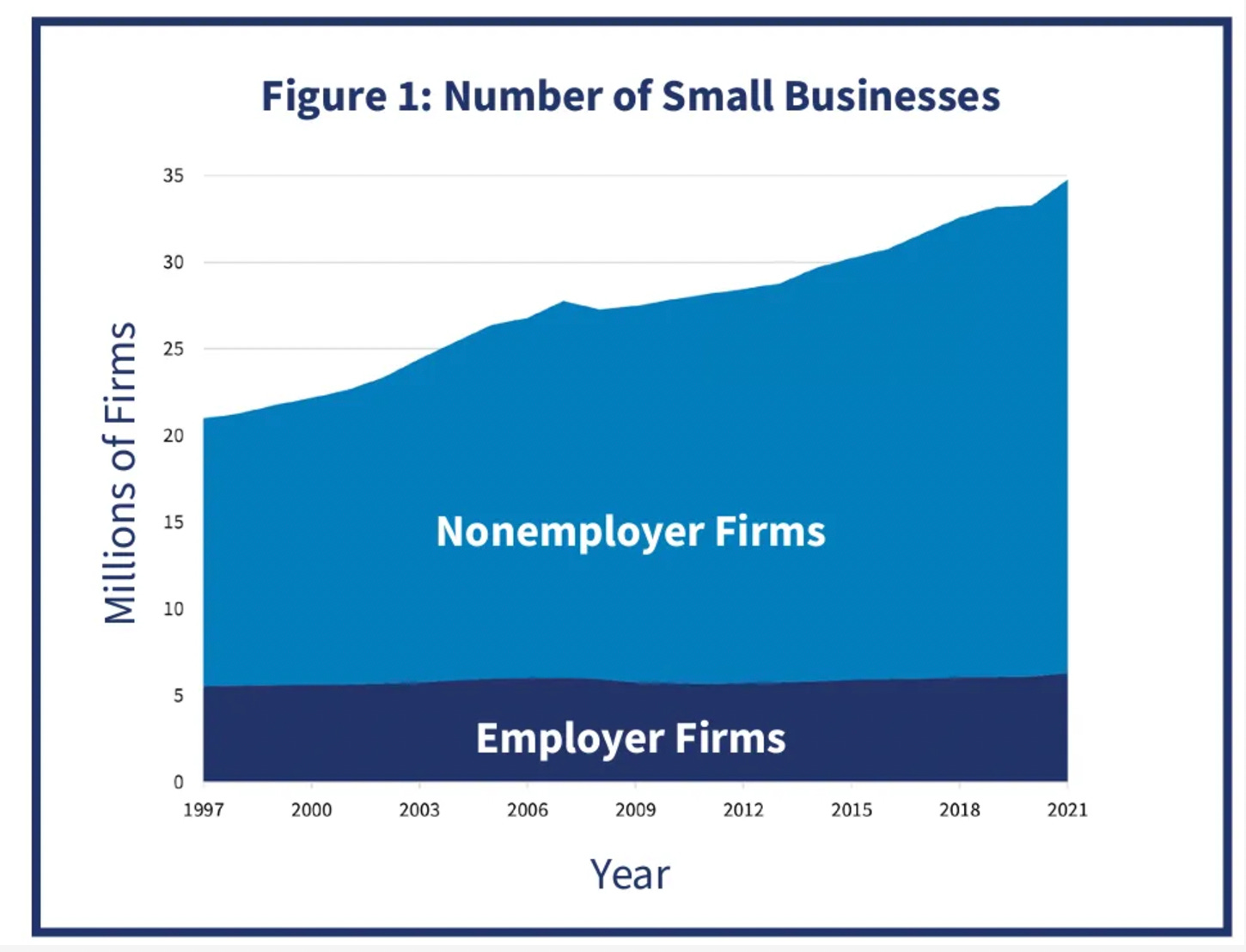

In fact, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy, it’s not the Main Street businesses with storefronts and employees that represent the majority of small businesses in the United States today. It’s nonemployer firms:

Quite a lot of us independent contractors are operating our one-person businesses not from Main Streets, but instead from vehicles or home offices along Maple, Elm and Oak Streets, in all kinds of neighborhoods all across the country.

This dispersed quality that we have—the very fact that we are independent contractors doing our own thing across hundreds of professions—means policymakers have to make a bit more of an effort to give us a meaningful seat at the table than, say, calling the head of a business organization with a K Street address in Washington, D.C.

But that’s exactly what has to happen if the administration truly wants to focus on the little guy and gal in the United States today. A heck of a lot of us are earning a living from America’s side streets—including on a lot of side streets located in swing states.

Swing-State Implications

Quite often in American politics, union members are held up as being representative of folks who wake up every day and get into the grind, working hard to earn a living. Union members are regularly referred to as shorthand for everyday working folks, as opposed to stock-market fat cats.

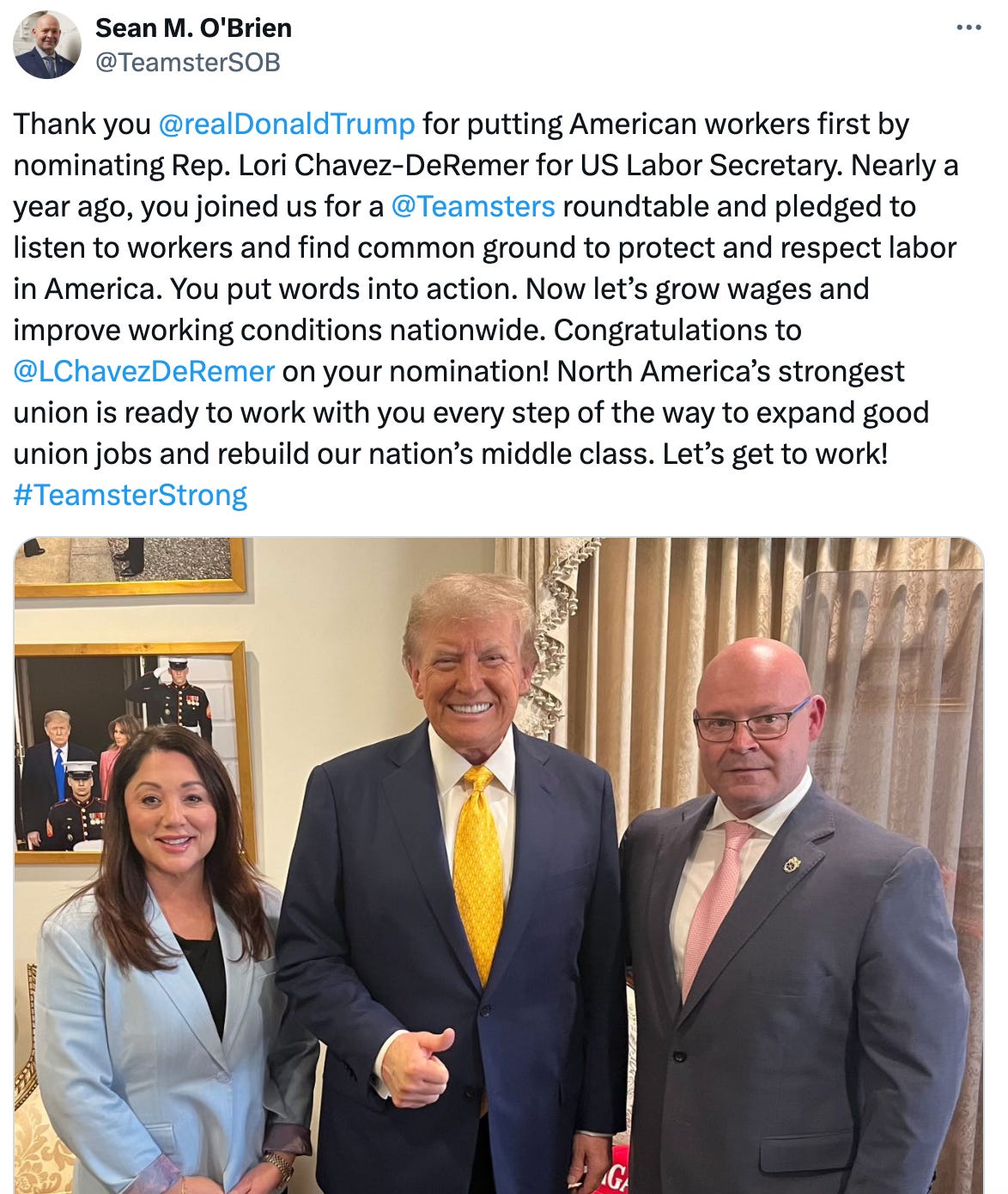

Those regular, hardworking Americans are the type of voters President Trump sought to curry favor with when he let Sean O’Brien, the head of the Teamsters union, have such a strong say in selecting Chavez-DeRemer to serve as U.S. Labor Secretary.

Look at the language O’Brien chose, about “putting American workers first,” back when Chavez-DeRemer’s nomination was announced:

The Trump-Vance administration seems to understand that appealing to Americans who work hard for a living means more than just getting rank-and-file union votes. Giving a seat at the table to advocates like the head of the International Franchise Association is smart, what with expectations for America to have about 850,000 franchises by the end of this year.

When you combine that figure with federal data showing there are about 14 million union members in the United States today, you get a decent slice of the electorate.

But anyone who looks a little deeper knows there’s an even bigger voting bloc just waiting to be identified and prioritized.

Consider the fact that nearly a full third of America’s 14 million union members are in just two states: California and New York. Franchises, of course, are located in every state—a characteristic that is also true of independent contractors. In fact, some franchise owners are, simultaneously, independent contractors. One sales pitch used to sell certain kinds of franchises is that you get to be your own boss without having to oversee any employees.

Other types of independent contractors include everything from owner-operator truckers to freelance writers to nurse anesthetists to real-estate agents. All in all, Americans who earn some or all of our income as independent contractors number 22 million to 72 million, depending on how the survey questions are asked.

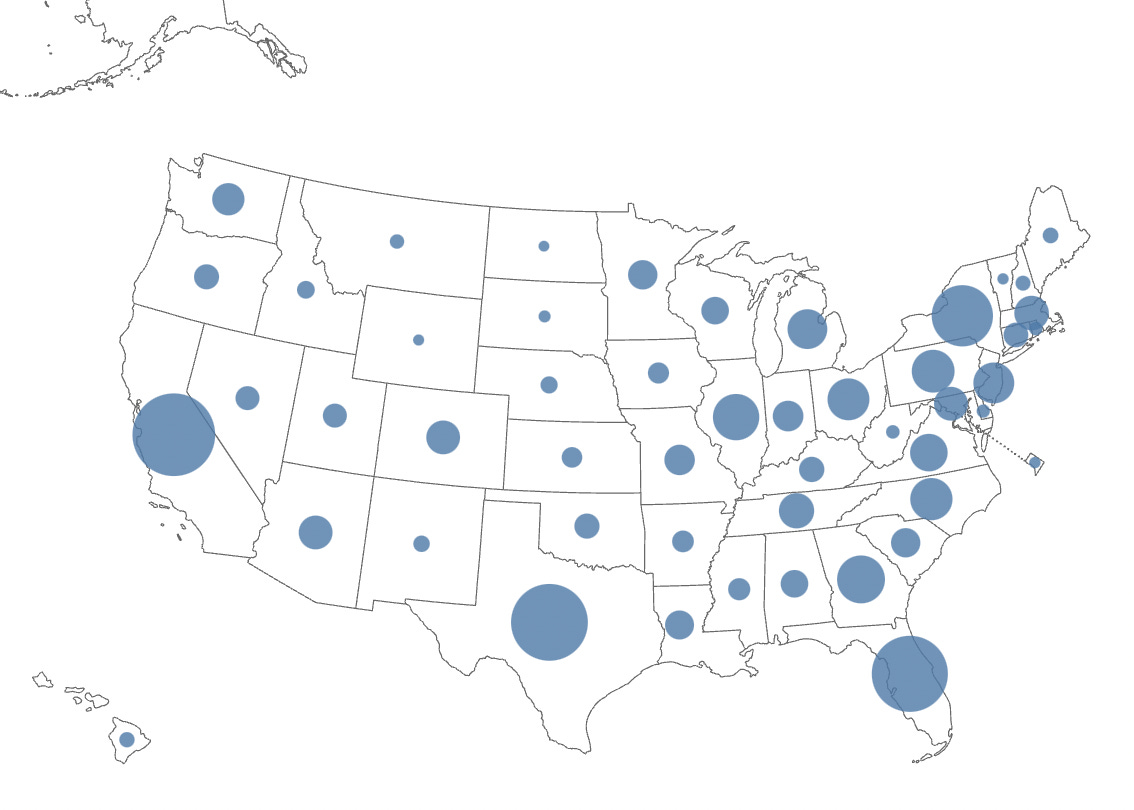

Independent contractors, when described as nonemployer firms, also have a statistically measurable presence in every state, including a significant presence in more than a few key swing states, according to the U.S. Census, which made this graphic:

In fact, there’s not just crossover between some franchise owners and independent contractors. More than a few union members are independent contractors, too, on nights and weekends. They have a day job as a unionized employee, and then work a side hustle as an independent contractor to help pay the bills.

This has been true for generations. My own parents were unionized public schoolteachers when I was growing up in the 1970s and ’80s. They had weekend gigs playing in bands, baking wedding cakes and the like.

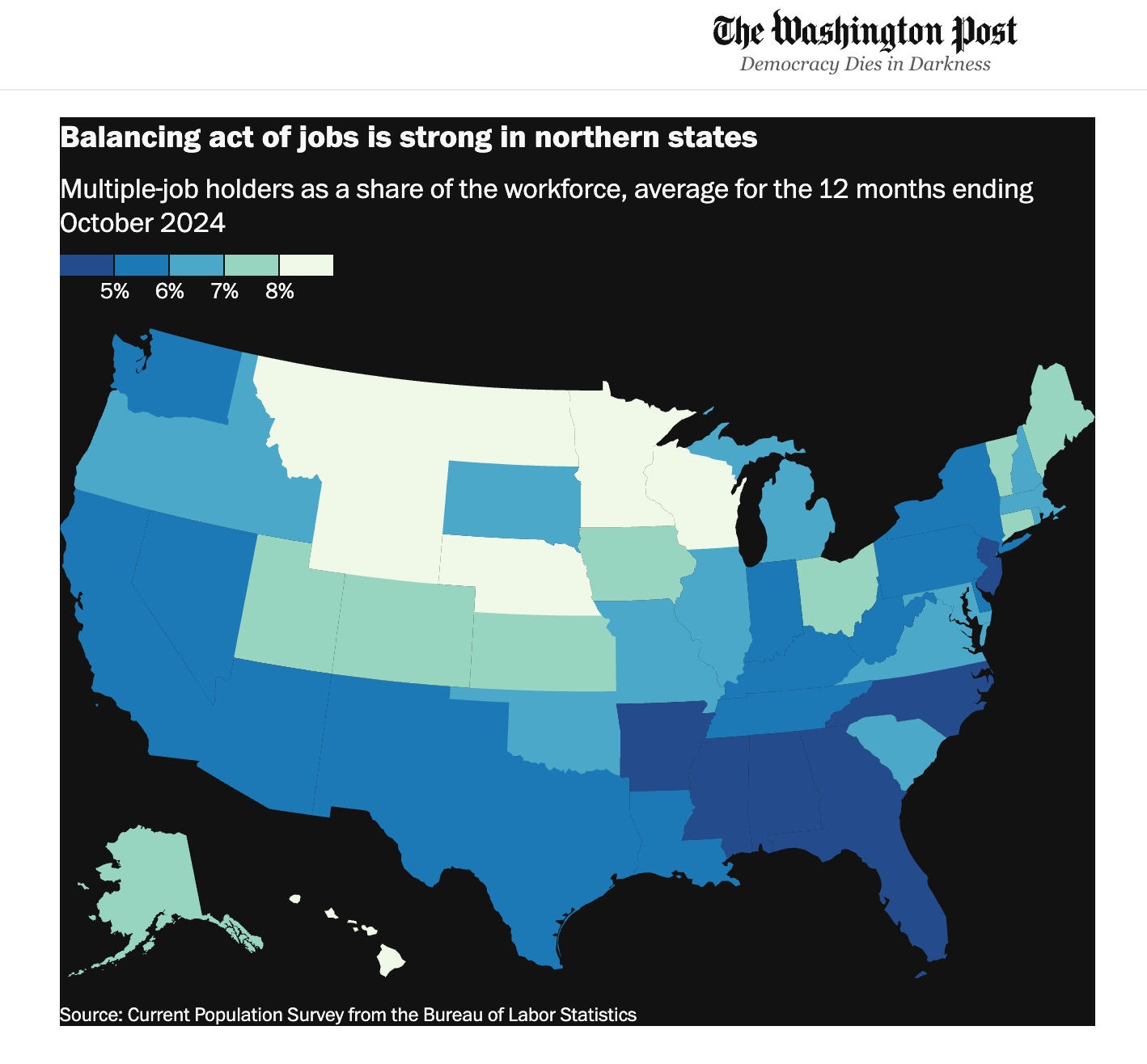

Just a few months ago, The Washington Post reported on the this same side-hustle phenomenon being true today. At least some of America’s side-hustlers are still unionized teachers, the article noted:

“A 2023 poll from Maryland’s teachers union with some 75,000 members found that 44 percent of public school teachers work more than one job to make ends meet.”

A graphic the Post ran with that story also made clear that a lot of Americans who fall into the side-hustle category live in key swing states:

Put another way, politicians who wish to gain voters should protect everyone’s right to be an independent contractor. Quite a lot of Americans are exercising that right as a way to pay for groceries and the mortgage every single day.

From a purely political perspective, thinking about the next big day at the ballot box, those same people are voting in swing states where pro-independent contractor policies would affect enough people to make a difference in election results.

According to a 2023 report by the American Action Forum:

In Georgia, there are more than 2.7 million independent workers

In Pennsylvania, there are more than 2.5 million

In Michigan, there are just shy of 2 million

In Arizona, the figure is more than 1.4 million

In Wisconsin, it’s about 915,000

In Nevada, there are about 660,000 independent workers

Creating policy that protects everyone’s freedom to earn a living in whatever way works best for us is just plain smart when it comes to electoral math.

It’s also good for keeping our economy going, and it’s what most Americans want. According to reputable data from multiple sources, protecting our freedom to earn a living in all kinds of ways is an 80/20 issue with the American public.

All politicians need to capitalize on this voting bloc is a little bit of effort.

Give Us A Meaningful Seat

Maple, Elm and Oak Streets need a meaningful voice in Washington, D.C. While we have seen some members of Congress—most notably U.S. Rep. Kevin Kiley, R-California, and U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy, R-Louisiana—do their best to stand up for us and protect us, we have yet to see a photo or a speech come out of the Trump-Vance administration that demonstrates a focus on independent contractors.

That’s what needs to change.

President Trump, during his first administration, made clear that he stood with us all when it comes to our freedom to earn a living. That’s what we need to see more of in this current administration. Get the independent-contractor policy right, and then get actual independent contractors into the policy meetings and publicity photos.

Need some names? Quite a few of us independent contractors have been raising our voices from California to Minnesota to New Jersey for years now, even making the effort—on our own time and our own dime—to write U.S. Supreme Court briefs and trek to Capitol Hill to testify before Congress, as ways of showing that we deserve a seat at the policymaking table.

The challenge is that we exist outside of the usual political swamp. Yes, it’s an easy play for politicians to talk with union leaders and lobbyists who earn their livings going to meetings and doling out support for political campaigns. Those folks are such a common presence in Washington, D.C., that our system has entire rules about how they’re required to behave.

Those of us who are independent contractors aren’t wandering up and down Constitution and Independence Avenues every day, going in and out of the Cannon and Longworth buildings to take meetings with legislative aides and other staffers. We’re instead in our vehicles on I-70 or I-95, or in our home offices in Boise or Topeka, working on our projects, marketing ourselves and negotiating deals to provide our services from Maple, Elm and Oak Streets all across the country.

Yes, that means it takes slightly more effort for Washington’s policymakers to find us. We’re not constantly up in their faces. They actually have to pick up the phone and call us to talk with us.

Is that really such a high bar to clear, though, when it comes to having smart, proportional and popular representation at the policymaking table in our nation’s capital? I think not.

The message the Trump-Vance administration is sending is that it wants to put Main Street ahead of Wall Street. Folks like Treasury Secretary Bessent and Labor Secretary DeRemer are delivering that message well.

It would be a pretty darn easy yes and, not a yes but, to include Maple, Elm and Oak Streets in that messaging too—and in the policymaking that comes next.